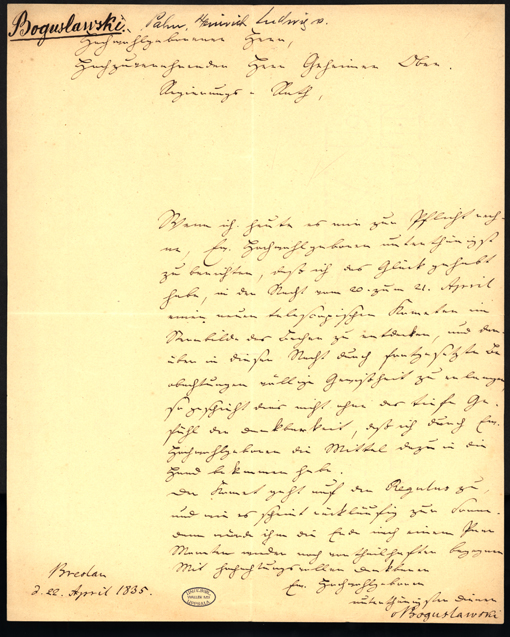

Letter from Palm Heinrich Ludwik von Boguslawski, German astronomer and head of observatory 22nd April 1835

Svensk version av detta blogginlägg

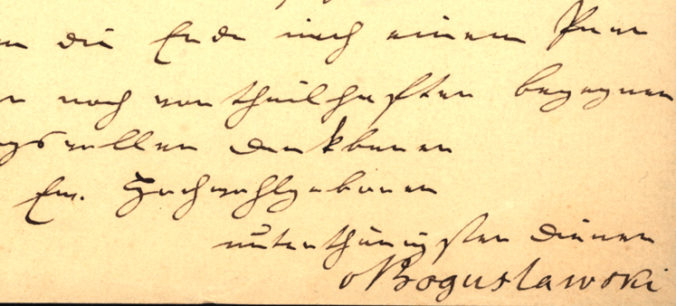

The letter is addressed to an unnamed Geheimer Ober-Regierungs-Rath. Boguslawski reveals that the previous night, the night between the 20th and 21st April 1835, he had discovered a comet in the southern constellation Crater ’the Cup’. The comet is moving towards the star Regulus in the northern constellation Leo. Boguslawski thinks it looks as though the comet will turn back in the direction of the sun and will be in a favourable position for observations within the next few months. He is writing the letter to thank the anonymous addressee for making this discovery possible, maybe by contributing financially to the observatory which had then been able to buy the telescope that Boguslawski used.

Astronomy belongs to the first disciplines studied in Europe. The subject was one of the seven free arts with, on the one hand arithmetic, geometry and music, and, on the other, rhetoric, dialectics and grammar. The celestial bodies – stars and planets – were thought to reflect or indeed influence life on earth. The sudden appearance of the comets, or ”hairy stars” from the Greek word meaning the long-haired one, naturally caused special interest. In folklore comets were seen as harbingers of doom or omens of war, illness or crop failure. Aristoteles thought them to be atmospheric evaporation and this belief was strongly held throughout the Middle Ages. Attempts to measure the distance of comets from the earth began in the 15th century. The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) found by observering the large comet in 1577 that comets were celestial bodies and that their orbits must be beyond the moon’s orbit, i.e. that their distance from the earth must be greater that the distance between the moon and the earth.

Research in the 17th and 18th centuries tried to find and improve methods for calculating the orbits of comets. The English astronomer Edmund Halley (1656-1742) discovered in 1705 that comets returned periodically. The comet that he predicted would return in 1758 very rightly did so and was subsequently named after him.

The composition, the density of the materia forming the head of a comet and the various kinds of tails became the object of study during the 19th century. It was discovered that the spectrum of the tail diverged from that of the head which was partly consistent with the sun’s since it derived from reflected sunlight. The Italian astronomer Giovannis Schiaparellis (1835-1910) discovered a relationship between meteor showers and comets in 1866. In connexion with this, large amounts of microscopic grains were found in the comets and it was also possible to conclude the presence of various gases.

At the beginning of the 20th century it was established that all comets appeared to belong to our solar system. This led among other things to the theory of a reservoir of comets which was formulated in 1950 and called Oort’s comet clouds (after the Dutch astronomer Jan Hendrik Oort, 1900-1992), and to the American astronomer Fred Whipple’s (1906-2004) model of the core of the comet as a ”dirty snowball” formed by ice and dust. Today it is believed that comets come from the colder parts at the periphery of our solar system and that they consist of the remains of the first celestial bodies in the planetary system which means that the original materia of our solar system is preserved in the comets. Therefore it is possible that they can have contributed the substances of which our oceans and atmosphere is made.

Boguslawski’s contribution to the research into comets places him in the tradition of the 18th century, despite his discovery having been made in 1835. The letter above is concerned with observing comets, calculating their orbits and periodicity. In order to be able to examine the matter of comets, Boguslawski would have needed photographic equipment to which he had no access.

Shelfmark: Waller Ms de-00418

The letter in digital form: Letter 1835-04-22, Wroclaw

Transcription

Hochwohlgeborener Herr,

Hochzuverehrender Herr Geheimer Ober-Regierungs-Rath,

Wenn ich heute es mir zur Pflicht mache, Eur. Hochwohlgeboren unterthänigst zu berichten, daß ich das Glück gehabt habe, in der Nacht vom 20. zum 21. April einen neuen telescopischen Kometen im Sternbilde des Becher zu entdecken, und darüber in dieser Nacht durch fortgesetzte Beobachtungen völlige Gewißheit zu erlangen, so geschieht dies nicht ohne das tiefe Gefühl der Dankbarkeit, daß ich durch Eur. Hochwohlgeboren die Mittel dazu in die Hand bekommen habe.

Der Komet geht auf den Regulus zu, und wie es scheint rückläufig zur Sonne. Dann würde ihm die Erde nach einem Paar Monaten wieder noch vortheilhafter begegnen.

Mit hochachtungsvollen dankbaren

Eur. Hochwohlgeboren

unterthänigster Diener

v. Boguslawski

Breslau

d. 22. April 1835

Palm Heinrich Ludwig von Boguslawski

Palm Heinrich Ludwik von Boguslawski or Palon Heinrich Ludwig Pruß von Boguslawsky, (1789-1851) was a Polish/German professor of astronomy and head of the observatory in Breslau. He had contact with the astronomer Johann Elert Bode (1747-1826), who was the head of the observatory in Berlin and who had published the first important star atlas. The two of them met at the Prussian Military Academy in Berlin in 1811-1812, when Boguslawski did his military service. Boguslawski was an artillery officer in the Prussian army in the war of liberation against Napoleon after which he resigned and settled on the family estate outside Breslau. He became the curator of the observatory in Breslau in 1831 and was appointed an honorary professor at the university there in 1836.

Boguslawski discovered a comet in 1835 and calculated its course. For this he was awarded the first gold comet medal and the comet was named after him. He describes this discovery in the letter shown above. He also made valuable observations and calculations of Biela’s, Encke’s and Halley’s comets, published articles in astronomy journals and participated in the publication of the journal Uranus during the years 1842-51.

- Ouranos, synchronistisch geordnete Ephemeride aller Himmelserscheinungen (Breslau: Grass, Barth & Co. Verl., 1832-)

- Uranus, oder tägliche für Jedermann fatliche Übersicht aller Himmelserscheinungen (Glogau: Flemming, 1845-)

Text and transcription: Hanna Östholm

Image: Uppsala University Library (Alvin)

This post has previously been published on the Uppsala University Library’s website 2014.