The Pantegni’s Progress: A Lost Encyclopedia Emerges from Fragments in the Uppsala University Library

by Monica H. Green, Arizona State University

Water Damage

In the 11th century, Europe witnessed the first of what would be several programs of translating Arabic science and medicine into Latin. When these works were imported into their new cultural milieu, their survival hinged on single hand-written copies, first of the original text in Arabic, and then of those first drafts of the translator’s Latin version. When a native North African, Constantine, arrived in Italy in the mid-1070s, he brought with him a cache of Arabic medical books that had never been seen before on the northern shores of the Mediterranean outside of Islamic Spain. Constantine, who soon became a monk at the Benedictine motherhouse of Monte Cassino, would spend the rest of his life translating these Arabic medical books into Latin.

But with one of his works, which he called the Pantegni—the Complete Art of Medicine—something happened that would frustrate his ambitions. The Pantegni was a large medical encyclopedia in two parts, originally composed by a Persian physician, ‘Ali ibn al-‘Abbas al-Majusi (d. ca. 982). The first part, in 10 books, addressed the theoretical aspects of medicine: basic elemental theory and physiology, anatomy, the causes of disease. The second part, which was also supposed to be in 10 books, addressed practice: how to maintain health (Book I), basic properties of pharmaceutical ingredients (Book II), fevers (Book III), general conditions of the body like leprosy (Book IV), diseases of the individual parts of the body, in head-to-toe order (Books V-VIII), surgery (Book IX), and compound medicines (Book X).

Constantine clearly had planned to translate the whole of the Pantegni, but as he was approaching the Italian shore, his ship was hit by a severe storm. The better part of the Practica was ruined. In the earliest manuscripts, we find only Books I, the first part of II, and, sometimes, the first third of Book IX. Constantine’s original copy of the Arabic text would have been written on either parchment or paper, since both materials were used in North Africa at this time. Paper (made of linen rag) would have been new in mainland Italy, however, so working with it may have been a particular challenge.

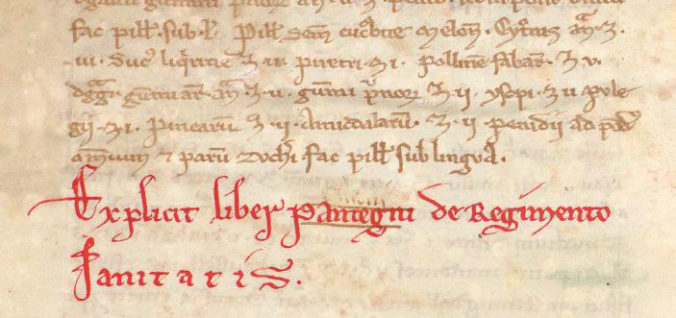

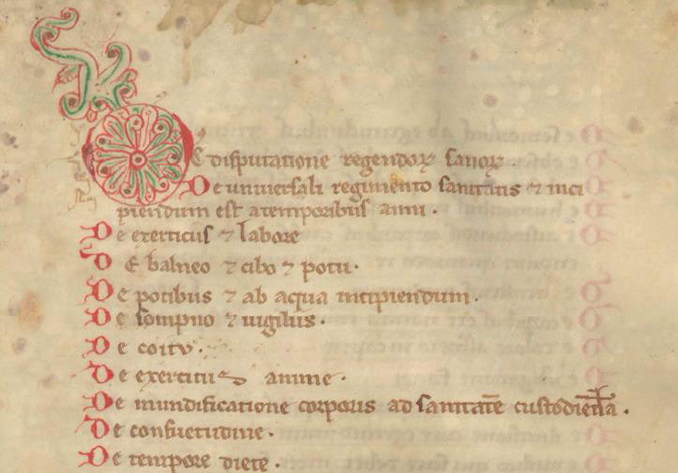

But Constantine persisted. A late 12th-century copy of the Pantegni, Practica in Uppsala University Library opens (fig. 1) with Books I and II, listed together as if they constituted a single book. But in fact, the Uppsala manuscript has more. Although somewhat cryptic, the Uppsala manuscript shows not simply an ambition to reconstruct the damaged text, which was partially successful, but traces of the compiler’s plans to add additional material.

fig. 1: Uppsala, Universitätsbibliothek, MS C 586, f. 81r (detail): the Table of Contents to Pantegni, Practica, Books I-II. This is the text on the regimen to maintain health.

“Notes to the Editor”

The historical clues embedded in the Uppsala manuscript are revealed by comparing it to others from the same time period. Below, in the table, are the contents of five manuscripts that document the process of planning the Practica’s completion. The first two, dating from the mid-12th century and now in libraries in Berlin and Oxford, present additional books that Constantine was able to salvage, apparently, from his water-damaged copy of al-Majusi’s Arabic original: Book VI, on diseases of the chest, and the better part of Book VII, on diseases of the abdomen. The Oxford manuscript also has the portion of the surgery, Book IX, that Constantine originally translated, which is documented in other, earlier copies of the Pantegni.

Table 1. Comparison of Manuscripts Documenting the Attempted Completion of the Pantegni, Practica

| Pantegni, Practica | Berlin, MS lat. qu. 303a, s. xii med. | Oxford, Pembroke MS 10, s. xii med. | Uppsala C 586, part 2, s. xii ex. | Munich, Clm 381, part 2 (ff. 89-156), s. xiii in. | Vatican, Pal. lat. 1304, part 5, s. xii ex. |

| I: regimen of health | — | — | X | X | X |

| IIa: “on testing medicine” (De probanda medicina) | — | — | X | X | X |

| IIb: [De simplici medicina] | — | — | — | — | [added by later hand: De simplici medicina] |

| IIc: [De gradibus] | — | — | X (1st sentence) | X (1st sentence) | De gradibus (complete) |

| III: on fevers and apostemes | — | — | [chapters on fevers, frenzy] | [chapters on fevers, frenzy] | [chapters on fevers] (following quire lost) |

| IV: diseases of the exterior of the body | — | — | — | — | — |

| V: diseases of the interior of the body (head) | — | — | — | — | — |

| VI: diseases of the respiratory organs | X | X | X | X | — |

| VII: diseases of the gastro-intestinal organs | X | X | — | X | — |

| VIII: diseases of the genitals and legs | — | — | — | — | — |

| IX: surgery | — | X | — | — | (added by later hand) |

| X: antidotary (book of compound medicines) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Other contents: | Alexander of Tralles, Practica | Masha’allah (“Messehalah”), Epistola in rebus eclipsis (tr. John of Seville and Limia, preface only); Liber flebothomiȩ (incomplete) | — | Tereoperica (Book I only) | Muscio, Gynaecia (and other texts added by later hands) |

So, Constantine was able to salvage portions of five of the ten books of the Practica after all. Half way there! The Uppsala manuscript, together with a similar one now in the State Library in Munich, then move beyond those of Berlin and Oxford, and show what the compiler planned to do next. And that was to go back and finish the still incomplete Book II, on medicinal substances. In both the Munich and Uppsala manuscripts, after the end of the portion of Book II of the Practica on “proving” medicines (describing the principal effects of medicines), there are three sentences forming the transition between the old material and the new:

“Hic autem finitur disputatio nostra de uniuersali uirtute simplicis medicine. ||

Est itaque incipienda singularum medicinarum disputatio de natura et ui et proprietate. ||

Quoniam disputationem simplicis medicine universaliter prout ratio postulavit, explevimus restat ut ordo de unaqua sequitur specie singulariter et cetera”

(Here ends our discussion of the universal power of simple [uncompounded] medicines. ||

And thus the discussion of individual medicines should begin, concerning the nature and power and character of them. ||

Because the general discussion of simple medicines depends on the types being used, it remains for us to explain each kind [of medicine] in turn, et cetera).

The first two sentences come from the original version of Book II. The sentence “Hic autem finitur …” (Here ends our discussion …) closes the De probanda medicina, which addressed the general characteristics of drugs. The next sentence, “Est itaque incipienda …” (And thus the discussion of individual medicines should begin …) clearly signals the next part of the text. But there was no “next part” in the earliest manuscripts of the Pantegni Practica. That’s what had been lost. Yet the editor or scribe had reason to believe it might yet be retrieved. In these earliest manuscripts, this sentence ended with two additional words: deo adiuvante, “God willing.”

What was that next section on individual medicines supposed to be? In al-Majusi’s Arabic original, that next section was called “On Simple Medicines.” Whereas the first section describes medicines by types (expectorants, laxatives, etc.), this second section described each drug individually (aloe, roses, zedoar). To replace it, the editor planned to use Constantine’s translation of a work called De gradibus (On the Degrees of Medicines) by Ibn al-Jazzar (d. 979), a physician in North Africa. And so, we find here in our Uppsala and Munich manuscripts, as our third sentence, “Quoniam disputationem …” (Because the general discussion …), the opening words Ibn al-Jazzar’s De gradibus (On the Degrees of Medicines).

But where was the rest of the text? That “et cetera” at the end of the third sentence was meant to flag, “and we’ll put in the rest of this later.” Yet it seems that “later” never came. Just as we use Post-It notes to flag where we plan to put new sections in our writing projects, so medieval writers used temporary notes, small scraps of parchment called schedulae, for notes that weren’t going to be immediately erased. But while the original compiler might know what those little notes meant, the scribe writing out a fair copy might not.

The initial scribe’s confusion can be seen in another part of the textual tradition. In several other manuscripts from this period—including one now in Bamberg, which captures the work of a mid-12th-century monk at Hildesheim named Northungus, and also the Codex Gigas (or “Devil’s Bible”) in Stockholm, the largest medieval manuscript in the world—we find the full prologue of the De gradibus. But still, the rest of the text is missing. Our Uppsala scribe, making his copy as much as a century after the “Post-It” note for the De gradibus had been placed, doesn’t seem to notice the error.

Completing the Pantegni Practica

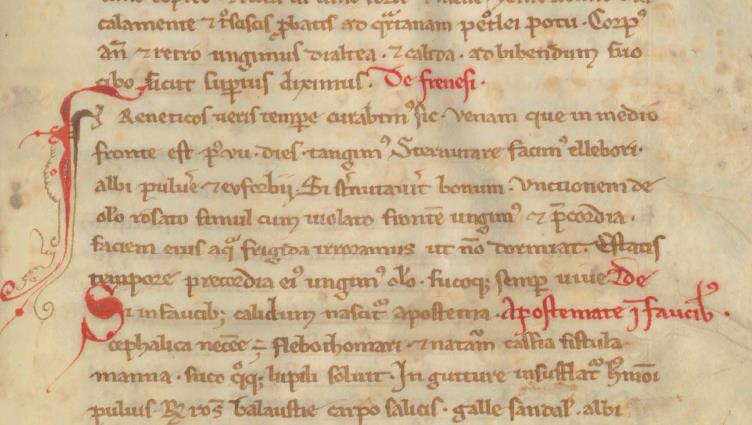

The place-marker for the De gradibus in the Uppsala and Munich manuscripts is followed by three short chapters on fevers, classified by their cyclicity: quotidian (daily), tertian (every other day), and quartan (every third day). Fevers were supposed to be treated in Book III of the Practica. Then comes a paragraph on frenzy, a topic that would be treated in Book VI of the Practica. Again, as with the excerpt from the De gradibus, it seems that these four brief chapters were placed in original exemplar copied at Monte Cassino as place-markers: signaling what the next section of the text was supposed to address. Interestingly, this sequence of chapters, grouped as if they were a unified text, is also found in Berlin lat. qu. 198, an odd manuscript made in France or Spain in the year 1131/32 that gathers together excerpts from a variety of different texts on medicine and the duties of running a rural estate. It, too, seems to have a lineage connecting directly to Monte Cassino.

The poor scribe copying out Constantine’s chaotic draft can, in the end, be forgiven, since from this point on, as reflected in the Uppsala and Munich manuscripts, he was copying Constantine’s original work as it had been intended. The chapter that follows on lesions of the throat (De apostemate in faucibus, fig. 2) opens Book VI of the Practica, on diseases of the neck and chest, showing that the full plan of a reconstructed Practica was taking shape.

fig. 2: Uppsala, Universitätsbibliothek, MS C 586, f. 130r, detail: transition between chapter on frenzy and first chapter of Book VI of Pantegni, Practica on lesions in the throat.

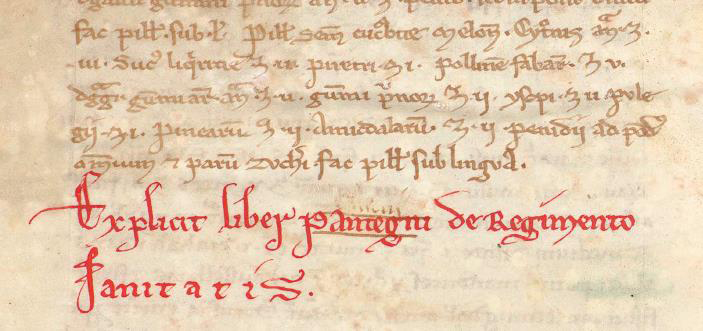

But the Uppsala scribe was, alas, himself dealing with a defective exemplar. In the Munich manuscript—and, indeed, in the Berlin and Oxford manuscripts we mentioned earlier—the whole of Book VI but also much of Book VII, on conditions of the digestive organs, had been copied. Our Uppsala scribe cut off his transcription of Book VI in the middle of chapter VI.6, in the chapter on harshness of the voice, signaling that he thought the text complete there. He ends with the bold words: Explicit liber Pantegni de Regimento Sanitatis (Here ends the Book Pantegni on the Regimen of Health, fig. 3).

fig. 3: Uppsala, Universitätsbibliothek, MS C 586, f. 132v, detail: colophon ending the Practica, Pantegni. In fact, the text breaks off here abruptly in the middle of Book VI, chapter 6.

Making Sense of Scraps

A modern scholar editing the Pantegni, looking for the “correct” form of the texts, would look at the Uppsala manuscript, declare it defective, and then just set it aside. For the historian, however, these “defects” tell a story. Why was the Pantegni, Practica allowed to leave Constantine’s desk in such an incomplete state? Perhaps the answer is simply that he died—leaving a copy unfinished on his desk, with no one to explain to the poor scribe that those schedulae were reminders to finish fleshing out the text, and not the main text itself.

Our story of the reconstruction of the Pantegni Practica doesn’t end here. Another manuscript from the late 12th century, now in the Vatican, preserves some remnants of the patchwork Practica, but here, the whole text of the De gradibus is present. Then, remarkably, another editor several decades later discovered a text that for the past century had been virtually unknown. This was Constantine’s translation of the De simplici medicina (On simple drugs)—yes, that second half of al-Majusi’s original Book II that had previously been given up for lost! Somehow, miraculously, Constantine had been able to repair the damaged copy from the shipwreck, or obtain a new one. By the time we get into the middle of the 13th century, a whole ten-book version of the Practica has been patched together, using selections from Constantine the African’s other works to make up for all the other material that couldn’t be recovered.

The discovery of the text of the Practica of the Pantegni in Uppsala C 586, precisely because it is incomplete, helps us reconstruct something more about what Constantine and his assistants were doing at Monte Cassino. They recognized how much wisdom was contained in al-Majusi’s original Arabic text, and they went to extraordinary lengths to reconstruct the lost or damaged text. That a record of that labor should now be found in a university library in Sweden is testimony to the far-reaching impact this monk from North Africa had.

—

Further Reading:

Constantine the African is a figure about whom we still have a lot to learn. The following studies can tell you more about his major work, the Pantegni, about the context of Monte Cassino in the 11th century, and about the larger context of learned medicine in the “long 12th century” in western Europe.

Charles Burnett and Danielle Jacquart, eds., Constantine the African and ‘Ali ibn al-Abbas al-Magusi: The ‘Pantegni’ and Related Texts. Studies in Ancient Medicine 10. Leiden: Brill, 1994.

Monica H. Green, “Medical Books,” in The European Book in the Long Twelfth Century, ed. Erik Kwakkel and Rodney Thomson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, in press).

Monica H. Green, “Rethinking the Manuscript Basis of Salvatore De Renzi’s Collectio Salernitana: The Corpus of Medical Writings in the ‘Long’ Twelfth Century,” in La ‘Collectio Salernitana’ di Salvatore De Renzi, ed. Danielle Jacquart and Agostino Paravicini Bagliani, Edizione Nazionale ‘La Scuola medica Salernitana’, 3 (Florence: SISMEL/Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2008), 15-60

Monica H. Green, “Salvage from an Eleventh-Century Shipwreck: Lost Sections of an Arabic Medical Encyclopedia Discovered in Pembroke College, Oxford,” Pembroke College, Oxford, blog post, 02 December 2015, http://www.pmb.ox.ac.uk/Green.

Francis Newton, The Scriptorium and Library at Monte Cassino, 1058-1109 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Monica H. Green

Arizona State University

monica.green@asu.edu