Letter from Jean-Baptiste Bo, French doctor, revolutionary and representative of the people, 31 October 1793

Svensk version av detta inlägg

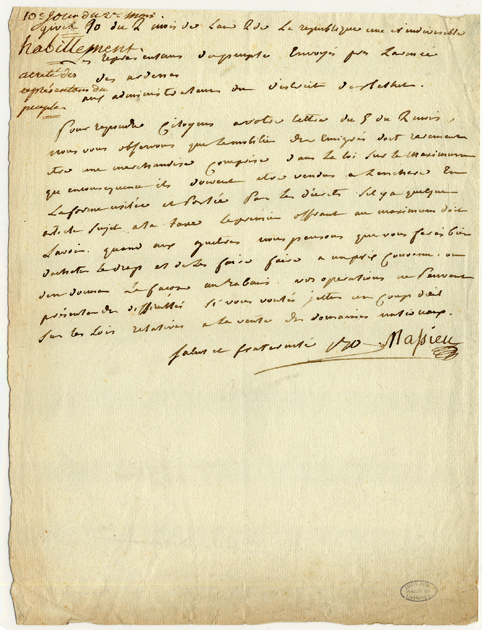

The letter was written in Givet, in the Department of Ardennes in northern France, and it is dated in accordance with the revolutionary calendar, ”10 du 2 mois de l’an 2 de la république une et indivisible”, i.e. the 10th day of the 2nd month of the year II of the One and Indivisible Republic. Converted into our calendar it was the 31st October 1793. The Reign of Terror had just been declared in the National Convention, it was two weeks after the Queen was executed and the guillotine was working full out. Jean-Baptiste Bo was working in Givet for the army of the Ardennes and as the people’s representative he has been asked by the administrators in another town’s district about property belonging to emigrants.

When the Revolution broke out in 1789 there were many people who, either in protest or later from fear, left the country. It was not just priests and the nobility but also merchants, farmers and workers. These emigrants were soon marked as ”Enemies of the Revolution”. There was a great fear of a conspiracy and the National Convention enacted more and more restrictive legislation against them. It was decided that the property of emigrants would be confiscated and sold and the emigrant act was passed on the 28th March 1793. Emigrants were defined as those who left French territory after the 1st July 1789 and who had not returned by the 9th May 1792, but it also included Frenchmen who were unable to prove that that had been uninterruptedly in France since 9th May 1792. According to the law they were now and forever banned from French territory, were stripped of their rights as citizens and their property fell to the Republic. An infringement of the ban would lead to the death sentence.

The letter refers to some pieces of confiscated furniture. They belong to the Republic and are to be sold, but the citizens in Rethel wonder if they come under the ”maximum law” passed on the 29th September, which stipulated a maximum price for all goods considered to be necessities. Bo replies that they are not affected by that law and may therefore be sold at auction. There can however be exceptions, for example goods that are to be taxed, and so the representative encourages his citizens to ”take a look” at the legislation which the Convention has passed concerning the sale of state property.

In the letter the sewing of damask (”guêtres”) is mentioned. Unfortunately the background to this matter concerning the damask is not stated, but Bo suggests that the administrators in Rethel simply buy the necessary material and get it sewn up for a pre-determined price or with a discount on the handiwork.

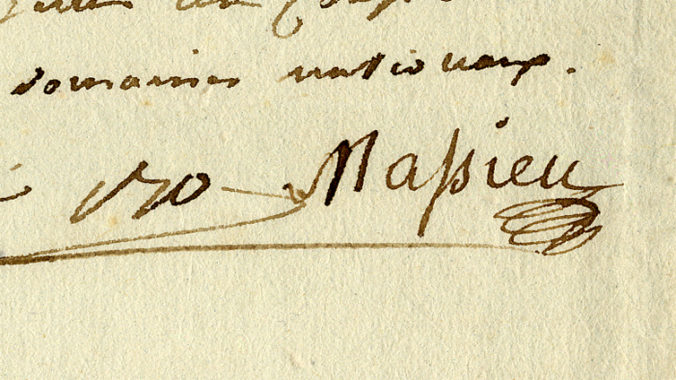

It is typical for the years of the Revolution that he uses ”Citoyens” as a term of address for the sake of equality and to mark the discontinuation of all kinds of privileges, replacing as it does titles and other polite phrases and which, in this case, gives the letter the stamp of officialdom. In a similar vein Bo ends his letter with the simple – but significant – words ”Salut et fraternité”. Thereafter come the signatures. Beside Bo’s own signature is that of Jean-Baptiste Massieu. Massieu (ca 1743-1818) was one of the Catholic priests who joined the Revolution in 1790 and was elected as a representative of the people. In 1790 he was posted in the Ardennes. Incidentally only eleven days after the writing of the letter, he informed the National Convention of his intention to resign from his position in order to marry the daughter of the Mayor of Givet.

Shelfmark: Waller Ms fr-00952

The letter in digital form: Official document

Transcription

Givet, 10 du 2 mois de l’an 2 de la république une et indivisible

Les représentans du peuple envoyés par l’armée des Ardenes aux administrateurs du district de Rethel.

Pour répondre Citoyens à votre lettre du 5 du 2 mois, nous vous observons que le mobilier des émigrés doit rarement être une marchandise comprise dans la loi sur le maximum, qu’en conséquence ils doivent être vendus à l’enchère en la forme usitée et portée par les décrets. S’il y a quelque article sujet à la taxe le premier offrant au maximum doit l’avoir. Quant aux guêtres, nous pensons que vous ferés bien d’acheter le drap et de les faire faire à un prix convenu ou d’en donner la façon au rabais. Vos opérations ne peuvent présenter de difficultés si vous voulés jetter un coup d’oeil sur les lois relatives à la vente des domaines nationaux.

Salut et fraternité

Bo Massieu

Top left-hand corner, an explanatory note written in another hand:

10e jour du 2e mois

habillement

arrêté des représentans du peuple

”Guêtre” : damask

”Façon” : here meaning ”work”, i.e. the actual work carried out by the craftsperson when creating an object. In this case it is a matter of the price for the work.

Jean-Baptiste Bo

Jean-Baptiste Bo was born in 1743 in a small village in southern France and was working as a doctor at the start of the French Revolution. His early political involvement in the Revolution bears witness to his enthusiasm for the new ideas. He was elected as a regional representative in 1790, before becoming a member of the so called Legislative Assembly in 1791, which changed its name in 1792 to the National Convention. He was particularly concerned with social matters. Alongside Robespierre he was among the most radical delegates who sat highest up in the plenary hall and were therefore called the ”montagnards” (from ”montagne”= ”mountain”). He voted for the execution of the King. In the provinces, where he was sent to enlist new allies during the worst years of the Reign of Terror, he became infamous for the inveterate and merciless war he pursued against all the ”Enemies of the Revolution”, i.e. the rich, Catholics, but also all ”suspects”, ”egoists” or even the ”indifferent”. He transformed the Cathedral in Rheims to a warehouse for fodder and in the little town of Givet, where the letter was written, he confiscated all the silver and gold he could find, as ”state property” as decreed by the Revolution. He was among those who introduced taxes on wealth for the benefit of the families of volunteers and it was on his initiative that measures were taken for the creation of a national insurance fund.

After the fall of the ”mountain” in the National Convention and the arrest of Robespierre on the 27th July 1794, it became increasingly hard for Bo and his radical friends to sidestep the accusations from other parties. He was to have been arrested when the amnesty of 26th October 1795 saved him. But his political career was over. He accepted a post as the director of the Office of Emigration in the Ministry of Police, before he finally withdrew to Fontainebleau to practise medicine until his death in 1814.

Text and transcription: Caroline Chevallier

Image: Uppsala University Library (Alvin)

This post has previously been published on the Uppsala University Library’s website 2014.

0 kommentarer

1 pingback